Unity Farm and Earth Day

To commemorate Earth Day, we revisit the history and wonder of Unity Farm, which was begun and maintained with an intentional and celebrated respect for the earth.

It was the summer of 1919 when Unity cofounder Charles Fillmore and his sons, Rickert and Lowell, discovered a 58-acre tract of land that would befit their plan for Unity to have a space separate from the headquarters at 917 Tracy in Kansas City.

They took possession of the property, located 18 miles southeast of the city, in March 1920, launching what would become known as Unity Farm. The subsequent purchase of 12 surrounding farms would expand the Unity footprint to nearly 1,500 acres.

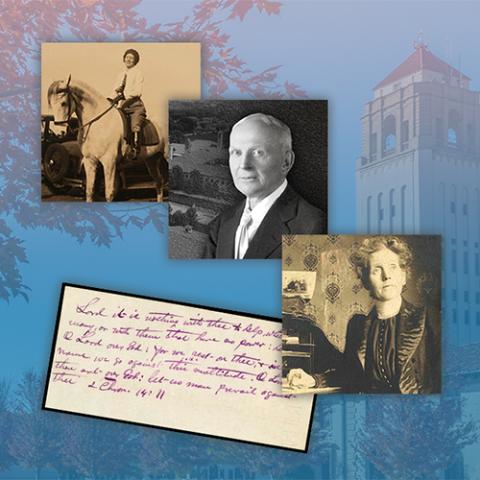

Practices at Unity Farm modeled the movement’s dietary and ecological priorities. Founders Charles and Myrtle Fillmore were vegetarians and encouraged Unity Farm workers to become vegetarians as well.

Much of the focus was on fruit and vegetable crop production. The farm’s orchards included 7,500 apple trees, producing a wide variety of apples. At peak, the trees yielded 75,000 bushels and 100 gallons of cider per year.

There were also cherry and plum trees scattered throughout the farm, a 400-tree peach orchard, 12 acres of grapevines that yielded 60 tons of grapes, and fields of oats, wheat, corn, asparagus, strawberries, and soy beans. One season, in 1928, workers experimented by planting 15 acres in sorghum cane.

Production at Unity Farm, which also supported a poultry house of 2,000 white leghorn hens, helped sustain the meatless menu at the Unity Inn restaurant at 9th and Tracy in Kansas City, wrote M.E. Ballou in 1926 in Jackson County, Missouri: Its Opportunities and Resources. (The Inn was one of the largest vegetarian cafeterias in the world, serving as many as 200 at each seating.)

To protect the pristine woodlands and rolling hills, Unity workers took great care to develop the farm only with what nature would provide. For example, streams were used to provide water for irrigation. In 1927, with the construction of a dam 530 feet long and 45 feet high, these same streams filled a 75 million-gallon reservoir that would be filtered for drinking water.

As more people lived at Unity Farm, demand for water grew.

Water well drilling on the acreage sometimes struck oil and natural gas, giving Unity the ability to use its own oil wells and natural gas supply lines to service the lanterns throughout the farm.

As many as 15 buildings were heated by gas from the 500-feet-deep natural gas wells that produced constantly, according to Jackson County, Missouri: Its Opportunities and Resources in 1926.

Also in the 1920s, Unity Farm built a three-mile road without disturbing the natural setting, and paved it with native rock from its own crusher. Unity Farm stone masons fashioned the rock to build rustic pools, walls, and bridges.

When a severe drought in the late 1930s killed a large number of black walnut trees on Unity Farm, workers felled the dead and dying trees and used the Unity sawmill to salvage more than nine miles of board feet of prime walnut lumber. The lumber would be gleaned for beautiful woodworking projects, and new trees would be planted to replace those taken in the drought.

Further, Unity used a native limestone quarried from outcroppings on its acreage for several construction projects. The yellow and white stone had a texture resembling the travertine limestone used in buildings in Italy, and can still be seen in the balustrades and fountains on today’s Unity Village grounds.

The award-winning Unity Village Hotel and Conference Center exemplifies the ongoing environmental stewardship demonstrated by the first generation of Unity.

When the 33,000-square-foot facility opened in 2006, it was one of the first Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED)-certified “green” hotels in the Midwest.